Natural Gas Prices: Just Produce Less

Written by Catherine Elder

Low prices often bring headlines that producers will shut-in wells to reduce supply until prices rise. Just produce less and prices should increase. But it almost never happens. Let’s talk about why.

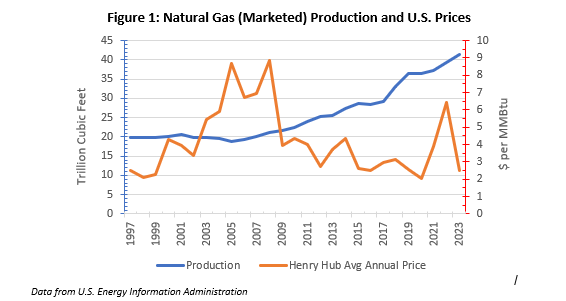

All of these reasons come down to practical reality. Let’s start with some data. Figure 1 gives natural gas production and annual Henry Hub prices back to 1997. The prices are in nominal dollars, but that won’t change any conclusions here. Production went up, pretty consistently over the 25 years. Now look at prices: they move up and down, but it sure doesn’t look like producers have shut in enough to lower production during low price periods.

First, the producer has expended capital to drill those wells. Sometimes the capital comes from cash the producer had on hand. More likely, it can from equity (stock) sales proceeds or from bank loans. They need cash flow to pay those loans and pay dividends to shareholders. So, while a producer might need a sales price of $3 per MMBtu to “break even,” that producer is still better off receiving say, $2 than no dollars: some money is better than none.

Second, that producer may also have hedged the sales price by using a forward sale and locking in price. BP CEO Murry Auchincloss, for example, said his company had done so in BP’s May 7, 2024 Q1 earnings call. With higher prices locked in, the producer has no need to curtail production.

Third, unless a producer has automated controls in place (and most newer wells likely do), reducing production means sending a worker out to every well and turning the valve handle to choke off some of the gas flow. And later sending a worker out to re-open the flow.

Fourth, the ownership of many wells is split among multiple parties. Selling a piece of the well to a third-party mitigates operating risk and produces an immediate shot of cash flow. Where ownership is split, no individual owner can shut down the well unilaterally. Instead, all must agree. But each owner likely faces different cash flow and payment obligations such that one of them may need the cash flow from selling the production. Never mind the fact that such discussions might raise collusion or anti-trust allegations.

Fifth, shut-ins damage the formation’s ultimate total production. This is harder to explain non-technically, but think of a well as a straw. The pressure downhole is higher than the pressure at the earth’s surface; this pressure differential is what allows gas to flow up the well. To get to the well, the gas sits in the pores between rocks. Permeability is the degree to which gas can migrate through the pores so that the gas can reach the well. In nearly every well some water comes to the surface with the gas – sometimes the water is more like a brine. Shutting the well changes those pressure differentials so that more brine accumulates near the well, and brings solids with it that clog the rock pores and well bottom perforations, blocking access to some of the gas. Some of this can be remedied by recompleting the well, but that’s additional capital expenditure. You can find a more technical explanation here. Bui, et. al. (2022) estimated the reduction in ultimate production could range from 20 to 40%.

Sixth is oil. Gas is often produced from wells funded by the search for oil. The producer was after oil but wells bring to the surface various hydrocarbons, as well as water, helium, nitrogen and hydrogen sulfide. The gas produced is often economically inconsequential because oil sells at multiples above the gas price. Gas today is under $2 per MMBtu, while oil sells at $78 per Barrel. There are roughly 6 MMBtu in a barrel of oil. Price parity on an MMBtu basis implies that a barrel of oil should cost 6 times more than natural gas. Figure 2 gives the oil to gas price ratio back to 2010. The data shows that oil often trades for much much more, averaging over $21 per MMBtu (shown in that red dotted line). Oil rocks: as long as oil prices remain high, drilling will continue.

Seventh. We’re up to seventh! Drilling programs are funded well in advance of the market’s setting of monthly spot prices. Leasing land, getting permits, scheduling the crew to spud and drill the well, then the other crew to hydraulically fracture and complete the well – all this is scheduled and contracted out, with drilling capital budgets announced in corporate earnings calls perhaps a year in advance. Hard to move it by much. Some producers will, though, delay completing their wells. About 2/3 of the cost is for completing, which is perforating the well casing string and fracturing the rock formation, so a delay will help spread that cost out over a longer period and may reduce short-term capex. EIA tracks wells drilled but not completed (known as “DUC’ wells). The data shows the current inventory of DUC wells to be about half what it was in late 2019 before COVID caused lockdowns and slowed work. This current inventory, however, is about the same as ten years ago.

Bottom line: shutting in natural gas production during times of low prices is not as easy as it may sound.